“Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World”

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

December 13, 2015 – March 20, 2016

By: Doug Hall

Imagine a visitor from another planet touching down and arriving at a single point in our civilization and finding

only !figurative artwork as evidence of our existence. And then picture that individual holding in his or her hands, a

bust of bronze sculpture so human-like, proportional, and with such detail of facial features that the wisps of hair

across a cheek are shown, and examples of expressions of subtle sadness and bold assurance are revealed. It

would be approximately 340 to 50 B.C. – the height of the Hellenistic Greek period, revealing of the !nest bronze

busts and full standing sculptures of the human form, epitomizing the high point of all cultural artistic

development, as measured against any other period of civilization, including our own. Now – fast forward to today,

and find some 50 such remaining examples (actually 1/3 of all known pieces on the planet) on display, in a one of-

a-kind, exceptionally curated and beautifully displayed exhibit

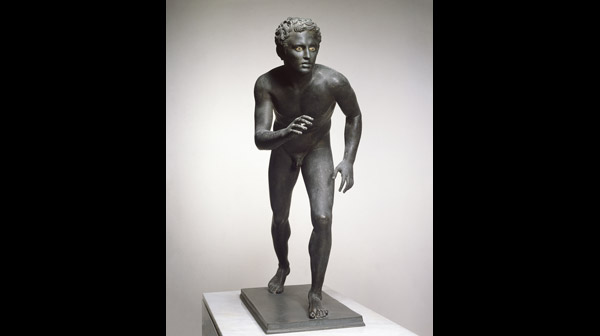

Unknown Artist (Hellenistic Bronze) Statue of a Runner, 100 BC- AD 79 Bronze, stone, and bone

The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C has organized a remarkable collection from museums around the

world, that highlights the accomplishment of skill and cultural advancement of this brief moment in time. To reinforce

the uniqueness of this opportunity, the Director of the National Gallery, Earl Powell, points out that “this is

the first time so many (Greek) bronzes have been gathered together from Europe, North Africa and the United

States.” Here now on display, in an intimate gallery space, away from the hoards of visitors in the main gallery

spaces at the National Gallery of Art, is an exquisite exhibit o”ering a once in a lifetime opportunity to see these

precious and historic works of art.

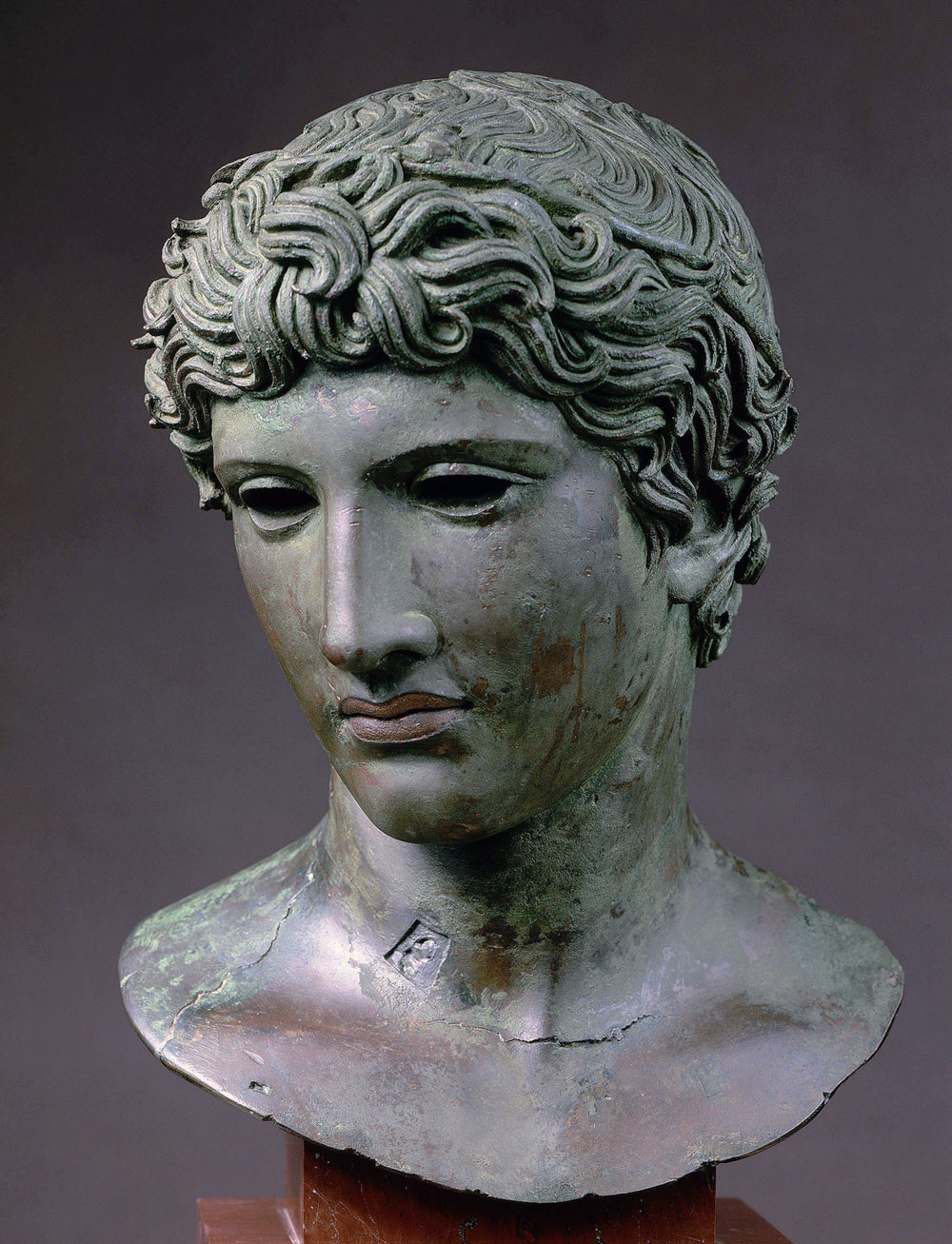

Unknown Artist (Hellenistic Bronze) Portrait of a Man, c. 100 B.C. bronze, copper, and stone

In addition to the rarity of this circumstance, the viewer is allowed an up-close and direct experience of

examination as most of these sculpture are “in the round”(i.e. fully 3 dimensional), and with many of the larger

standing bronze sculptures, and busts, out of plexi-cases. It is a unique chance to see, with un-obstructed sight

line, the detailed skill of artistry, craftsmanship and technique that rivals any period in cultural achievement and

most importantly the innovation of true human likeness. In the words of the in-gallery curator guide, “this is the

birth of portraiture…a speci!c sense of personage… individualized…features of an actual human being.” This is

an all new approach and execution. Hellenistic sculptors are no longer depending on an idealized figure –

replicated over and over again. But instead, the artist is responsible for the accuracy and depiction of his subject.

Unknown Artist (Hellenistic Bronze) Victorious Athlete “The Getty Bronze”, 300 – 100 B.C. bronze

The move to bronze as a material, during the Hellenistic period, allowed Greek sculptors highly specialized in this

medium, a vehicle to o”er greater human likeness and expressiveness that marble statues of the past could not

provide. The evolution to the lost-wax casting process for bronze (a multi-step casting process that utilizes

poured molding from wax to molten bronze transfer) was the key technique and innovation, allowed sectioning of

molded arms and legs and torsos that would be later attached, to become a giant full standing human sculpture

maybe 12 feet or taller. To further human-likeness, the bronze facial features were etched with whiskers, eye

brows, facial scars and marks, as well as cosmetic additions of lips of molded copper, eyes made of marble or

precious stone – all to further exhibit human qualities.

Unknown Artist (Hellenistic Bronze) A Youth “The Beneventum Head”, c. 50 BC bronze and copper

Thousands of these bronze statues existed during the Hellenistic period (roughly between the death of Alexander

the Great in 323 B.C., and the control of Greece by the Roman Empire, by the time of the Battle of Actium in 31

B.C.). Hellenistic kings, seeking representation for power in public works, after Alexander’s empire was broken-up,

used the display of over-sized bronze statues of themselves as a way to assert dominance and self-propaganda

in likeness as war heroes and statesman. And with wealth – patronage of the arts grew so that establishment

families could show-o” class position with such exhibition of likeness. Also, sporting events developed as a very

honorable and important feature of ancient Greek society (witness the invention of the Olympiad – pre-cursor to

the present-day Olympics); so many athletes, in all forms of physical competition, would have been erected

around city-states and stadium arenas.

Cavallo Riccardi Horse Head “The Medici Riccardi Horse”, c. 350 B.C. bronze and gold overall

So why are just a few statues and fragments left remaining? As the curators of this historic exhibit remind us: there

were practical reasons – the need to efficiently re-use materials was one of them. New bronzes figures could be

re-cast by melting down existing statues, as the course of one leader became favored over someone in the past.

And equally, in companion, was the constant need for weaponry for internal order and defense from external

enemies – bronze statues were liquefied to be forged into armament; becoming parts of swords, shields and

helmets. In fact, most of what is on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., through this special

exhibit, and elsewhere in selective museums around the world, is the result of happenstance. Findings remain few

and through mostly accidents; A sunken ancient trade ship dumps its load and a discovery is made at the bottom

of the Mediterranean sea in modern times, or buried in the volcanic eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in Herculaneum in 79

A.D., (now heavily excavated sites), a statue is found – accompanied by a painstakingly restorative process. What

was once a familiar and everyday part of the ancient Greek Hellenistic landscape is now a small treasure of

examples.

A very hands-on, interpretative audio guide tour coupled with an excellent exhibit gallery wall rendering of an

ancient Greek city-state or polis, provides a glimpse of what some of the temples, market places and government

and administrative buildings of these city-states looked like, adorned with hundreds of bronze sculptures.

Unknown Artist (Hellenistic Bronze) Artemis with Deer, 100 BC- AD 100 bronze height: 48 3/4 inches

Alas – here is your chance to see the few examples that will, if preserved, tell future generations of a time in

ancient history, where a culture reached a stellar high point. These bronze sculptures speak back to you in terms

of artistry, skill and presentation of the human form in excruciating detail, revealing emotions and a shared human

nature. “The Power and the Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World”, at the National Gallery of Art, in

Washington D.C., provokes reflection and amazement as we the viewer are provided a treasured glimpse

backwards into the zenith of Hellenistic Greece.