Known for his lyrical and relaxed style on the tenor saxophone, exceptional improvisor and seminal influence on his instrument, Lester Young, “The Prez,” was interviewed in a Paris hotel room just two months before he died. In response to a question about big bands like Count Basie’s Orchestra, where Young had become famous, he stated, “I don’t like a whole lot of noise – trumpets and trombones – I’m looking for something soft. It’s got to be sweetness, man, you dig?”

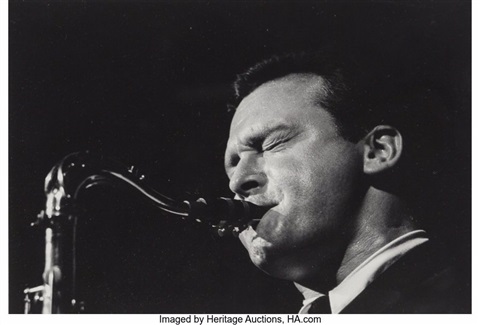

Stan Getz, a much younger next generation tenor sax player, was listening and heeded Lester Young’s advice throughout a career that earned him a legacy of being one of the greatest tenor saxophone players to pick up the instrument. Dizzy Gillespie, legendary Bebop pioneer, band leader and innovator on his trumpet, whom Getz recorded with in the 1950s, stated “his major contribution to jazz was melody. He was the best melody player in jazz. And an incredible soloist, but I loved his melodies. He’s right up there with all the greats. You can’t get any better than him.”

(www.nyt.com/1991/06/08/obituaries/stan-getz-64-jazz-innovator-on-saxophone-dies.html)

In reference to horn styles, during the same period of Getz’s career, you had Charlie Parker squeezing out as many rapid-fire Bebop notes in a bar as humanly possible, and then later Miles Davis, using just three long sustained modal notes to fill the same phrase. Stan Getz will step in and instead deliver a harmonic melody that romanticizes and floats above the music with a cool sexy tone – but never sentimental. Listening to the note construction and seductive tone and immaculate phrasing of the iconic Getz solo on “The Girl from Ipanema” from Getz/Gilberto (Verve, 1964), his “sound” is forever imbedded in your jazz listening ear.

Growing up in New York City during the Great Depression in the immigrant tenements of the Bronx, Getz’s family–and particularly his mother–encouraged him to play and he almost immediately showed exceptional aptitude for music. As cited in biography and interviews, Getz fell in love with the saxophone first purchased for him by his father at the age of 13, and he would practice eight hours a day. In a New York Times interview in 1991, (NYT, June 9, 1991), just before his death, Getz talked about the tough neighborhood and times he grew up in:

“Most of the kids in my neighborhood in the Bronx either became members of Murder Inc. or cops. There wasn’t much choice.” Though a fondness, love and respect for his mother shines through in this interview, with some amusing recollections, “I would practice the saxophone in the bathroom, and the tenements were so close together that in the summertime, when the windows would open, someone from across the alleyway would yell, ‘Shut that kid up,’ and my mother would say, ‘Play louder, Stanley.’ My folks were proud.”

In 1942, at the age of 16, Getz would join his first professional band under Jack Teagarden, a premier trombonist and vocalist of the period. The opportunity presented itself when the regular tenor sax player failed to show up. Getz recalled, “Someone let me use their horn so I sat in, read their book.” He would be a quick study, learning by ear with only several takes.

He would be offered the job on the spot. Getz would enter an adult world, in a touring band, as a teenager without any “real world” experience, under the wing of seasoned musicians. This was an abrupt lifestyle change for an impressionable young musician, on the road without family and the example of much older peers, which included the introduction to a long-term addiction to heroin.

After a one-year stint with Teagarden, Getz would move on to play with many of the top-tier big band leaders of the period, from roughly 1944-49. He would build an impressive resume of performance experience with Nat King Cole, Lionel Hampton, Stan Kenton, Jimmy Dorsey and Benny Goodman.

Most importantly, for career development and recognition, Getz was given a soloist opportunity with the Woody Herman Band (known informally as “The Second Herd”) from 1947-49. He was to receive his first widespread public attention, along with Herman’s other very talented horn lineup including Serge Chaloff, Zoot Sims and Herbie Steward – who were collectively known as “The Four Brothers.” A masterful arrangement by Ralph Burns provided an early signature solo by Getz, only 20 at the time, that was captured on a recording session with Herman’s “Summer Sequence Part IV,” reviewed by many jazz scholars as sublime and elegant. Jazz Critic Marc Myers stated, “The big surprise came two minutes into the recording, when Getz took a beautiful, yearning eight-bar solo that was considered revelatory at the time.”

(www.jazzwx.com/2017/10/history-of-early-autumn.html)

“Summertime Sequence Part IV” then evolved into a secondary arrangement for Herman’s “Early Autumn,” which further distinguished Getz’s style, sound and vocabulary on the tenor sax and brought commercial attention to his playing chops. A now celebrated performance that revealed his personal tone: “featherlight, vibrato-less, and pure and showed the influence of his idol Lester Young.”

(www.britannica.com/biography/Stan-Getz)

In the 1950s, Getz would then step into the hard-bop period, leading quartets and recording and performing with many leaders and innovators of this genre, including pianists Al Haig and Duke Jordan; drummers Roy Haynes and Max Roach; and bassist Tommy Potter, all of whom had worked with Charlie Parker. Also, as an in-demand band leader of quartets and quintets, he made talent discoveries, including pianist Horace Silver’s Trio, guitarist Jimmy Raney, and trombonist Bob Brookmeyer. In addition, while in Los Angeles during the later ‘50s, Getz would also participate in several of Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts which included other famous performers including the Oscar Peterson Trio and Miles Davis.

Retreating from legal issues and professional demands, he took up residence in Europe from 1958 to early 1960 and continued to make well-respected recordings during this time with other American expatriates, particularly Oscar Pettiford and Kenny Clarke. His musical center was Copenhagen, Denmark, often at the nightclub Café Montmartre, where he worked on craft, played sessions with other European musicians, gave informal tutorials, and recorded. In a 1960 article in DownBeat Magazine, Getz was interviewed in Denmark and reflected on being away from the stress of constant performance schedules. “My music gets better when I have time for meditation and working new things out. I have been working a lot with my tone over here. I’ve been trying to set it more naturally. I’m trying to move away from too much vibrato…I started off the wrong way, learning the practical aspects first. It’s a blind alley.” During this same period, a Danish jazz critic responded to the changes in Getz’s playing style thusly: “he has soul in every note he plays…Getz demonstrates that the modern school isn’t as bloodless as people have been thinking. He builds up his themes with unerring logic…giving his tone so much richness and fullness without vibrato.”

(www.downbeat.com/archives/detail/expatriate-life-stan-getz/P2)

Returning to the US in ‘61, he would team up with arranger Eddie Sauter to record Focus, an album that many jazz critics and fellow musicians of his generation regard as Getz’s masterpiece. With muscular orchestral string arrangements, his playing ranges in wide experimental directions, innovating against the backdrop of Sauter’s ballads. Jazz critic Stephen Cook describes Focus as “admittedly Getz’s most challenging date and arguably his finest moment.”

In the next stage of his career, Getz would find international fame and exposure via several Bossa Nova-based albums, including his first collaboration with jazz guitarist Donald Byrd on Jazz Samba in ’62, which earned Getz a Grammy for Best Jazz Performance in 1963 for the single Desafinado.

Following Byrd’s advice, who had been listening to this highly syncopated version of samba-based Brazilian music on a recent government-sponsored trip to Brazil, Getz would join the two pioneers of this unique Brazilian blend of music, Antônio Carlos Jobim and João Gilberto. This collaboration would produce a million-selling jazz album, entitled Getz/Gilberto, released in 1964. The release also featured Gilberto’s wife Astrud with the stunningly smooth and seductive vocals on Girl from Ipanema, which won the Grammy Award for Best Single. The recording would win the Grammy Award for Best Album.

He would also briefly join vibraphonist Gary Burton, taking a different direction from the current popularity and album sales offered through repetition of the bossa-nova rave.

Getz would then leave the sound and style of Bossa Nova entirely behind, to the disappointment of Verve Records, as he sought adventure with more modern artists, finding pianist Chick Corea, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Grady Tate, “all schooled in the ‘60s concept of rhythm-section freedom.” Getz’s first independent recording after his Bossa Nova fame was a complete departure, Sweet Rain (1967), seen by jazz critics as a secondary masterpiece alongside Focus (1961). Reviewed by AllMusic critic Steve Huey, he states, “The quartet’s level of musicianship remains high on every selection, and the marvelously consistent atmosphere the album evokes places it among Getz’s very best. A surefire classic.”

(www.allmusic.com/album/sweet-rain-mw0000188080)

Joining forces again with Chick Corea and the pianist/bandleader’s early jazz fusion formation of Stanley Clarke on bass, with Tony Williams and Airto Moreira on drums, Getz would record Captain Marvel (1972), which was a successful venture creatively, reestablishing his ability to change within new jazz directions. Though the compositions were mostly written by Corea, Getz was allowed to experiment with a sharper edge and faster tempo delivery, also using the Echoplex (a tape delay effect) on his saxophone.

Though in 1986 he would be inducted into the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame, the 1980s saw a return to a higher level of drug and alcohol abuse. The resulting combative and destructive behavior, leading to arrest and final divorce proceedings, would steal significant time away from productive musicianship and performance. But in keeping with his heroic reputation for stamina, he still turned out successful performances and additional recordings. His release Anniversary (EmArchy, 1987) garnered him a Grammy and an equally strong effort of compositions on Serenity (EmArchy, 1987), a live gig recording back at his old haunt, the Café Montmartre in Copenhagen, of which AllMusic critic Scott Yanow reviewed enthusiastically, “Getz…(who only had four years to live) plays in peak form, really stretching out…His solo on “I Remember You” is particularly strong.”

(www.allmusic.com/album/serenity-mw0000263596)

During this tumultuous period in his personal life, Getz did also find a home for his talent and instruction in the San Francisco Bay area, teaching at Stanford University as an artist-in-residence at the Stanford Jazz Workshop until 1988. In style, he had also returned to a pre-electric instrument period. “…to the delight of purists, Getz returned to traditional acoustic jazz instrumentation in 1981 and stayed with such arrangements for the remainder of his career, which included an association with Stanford University until his death.” Getz would die of liver cancer in 1991.

( www.britannica.com/biography/Stan-Getz )

In personality, he could be obstinate, domineering, and confrontational, yet certainly demanding of himself as a genius in phrasing and melody on his instrument. He was always in command of what he wanted to express on his horn and thereby an uncompromising musician to work with. Saxophonist Zoot Sims, who had known Getz since the Woody Herman band- period of the late ‘40s, was asked about his friendship with Getz and responded with a revealing quote, “a nice bunch of guys.”

Ultimately it is the melodic quality of Getz’s tenor saxophone that is best remembered – distinct, pure in tone, and effortless in delivery – as attested to by a wide range of listeners, jazz critics, and musicians. John Coltrane, a legendary saxophonist and a giant in all categories of jazz, once said of Getz’s style, “Let’s face it – we’d all sound like that if we could.”