When I started playing fast out in the canyon it just didn’t make sense at first. I had to stop and say ‘this doesn’t feel right’—like this open ravine with river doesn’t give a crap about bebop.

—Jon Irabagon

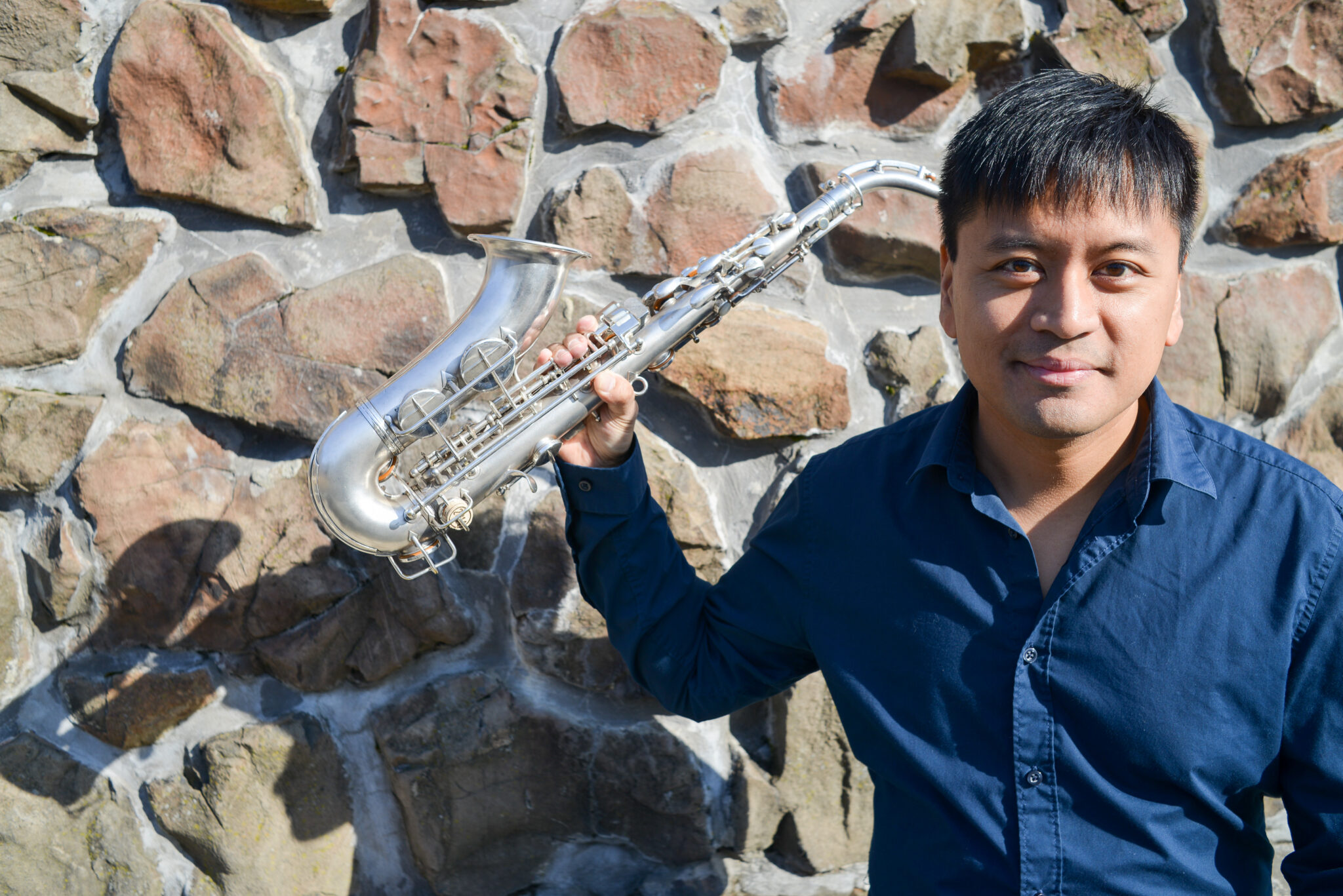

Finding a retreat into the Falling Rock canyon of the Black Hills National Forest for meditation and reflection, Irabagon found himself returning to this solitude with his tenor sax for 5-6 months, 6-7 days a week. This sojourn led him to reflect on the centennial of a major musical influence in his career: Charlie Parker. In different locations throughout the canyon—next to streams, in the wind or with the sound of bird song in the air-Irabagon re-interpreted a personal selection of Charlie Parker standards and recorded an album, Bird with Streams (Irrabagast Records, 2021) with the acoustics of this natural environment.

All About Jazz: How did the solitude of the canyon inform and influence your interpretations of these Charlie Parker standards?

Jon Irabagon: When I started going out to the canyon, a few weeks after we [Irabagon’s family] moved out to South Dakota, I didn’t have plans to make a solo record or to do anything Charlie Parker related at all. I was just lucky to have this space (Black Hills National Forest, S.D.), I could just park, do a short hike—and get right to where I needed to go and just relax. Over the course of being out there, about 5-6 months, 6 or 7 days a week, was intense. It was the most flex time and focus time I’ve gotten in years and during those months I started working on different aspects of my playing. I was composing, improvising freely, getting my soprano chops together, trying to get my sound going together and learn a bunch of tunes, re-visit a bunch of tunes—it was all in-compassing. Also, just to have some time to meditate and relax.

So during that time that I was out there, Charlie Parker’s centennial came, and I thought, let me re-visit some of these “heads”(i.e. melody) and some of these ideas. I was only going to do it for a couple weeks or so, but it felt like such a great re-connection with him and his music and what his music meant to me even, so I just kept running with it. So, by the time October came around I realized I’d been spending about a year and half out here for hours and hours every day, and I should record something just to have a document of my time out here. When I was trying to figure out what to record, I kept coming back to Charlie Parker tunes—thinking maybe I can put together a recording while working on a bunch of things using Parker as the springboard. I never would have imagined myself recording a Charlie Parker album in the first place, but it was one of the outcomes of my time out there. I’ve also got a quintet record coming out later this year from compositions I wrote there and a quartet album coming out hopefully next year, that’s already recorded. And all those compositions were written in the canyon.

I didn’t have a solo tenor album yet, so it let me highlight, and the Charlie Parker direction seemed to be the furthest thing from the other two recordings and was a huge challenge in and of itself. It kept me really focused preparing for the record.

AAJ: How would you express the meditation and reflection in the canyon on the Charlie Parker standards you chose to interpret?

JI: It gave me a chance to relax and reflect on life while being out there, and I didn’t really on-purpose throw all that into the record, but of course it’s all related. One of the intense parts of this was working on my time feel. Being a rhythm section in and of yourself, with these tunes in particular, most of them are standard forms —most of the time I’m playing over the forms. I think the meditation part was trying to get my time feel together. Trying to have a Zen-outlook and say—ok—float with the time and move forward with it and I think that’s probably the most palpable way that my solitude played out.

AAJ: What freedoms come from being without musical accompaniment?

JI: With 15 songs on the album, there are the Charlie Parker tunes, but I’m also trying to combine my better technique ideas with it. With Some of the tunes I’m focused with techniques ideas there—like if I’m going to play Parker’s “Moose the Mooche” with a rhythm section, I’m messing around using the sax as a middle tune sound generator—so that’s some of the freedom. Also I took segments and tried to make it a rubato ballad type of thing. I think having no conception with the challenging and freeing up—it freed me up a little bit. You still have to have responsibility for being exact for whatever melody, rhythm and harmonic aspects you want to get across. You have to be more responsible with it—melody, harmony and rhythm—but with that responsibility comes great freedom.

AAJ: The isolation and quiet of the canyon contrasts with Parker’s legendary fast-tempo bebop style of sax playing—how do the two co-exist?

JI: That’s actually really pertinent because when I first started going out there, I just started playing long tones and getting used to surroundings and seeing the deer walk by. I thought, maybe I can use this time to work on my fast tempo playing and get that together. When I started playing fast out in the canyon it just didn’t make sense at first. I had to stop and say ‘this doesn’t feel right’—like this open ravine with river doesn’t give a crap about bebop.

This is part of the music and I’ll keep exploring it, but it just seemed like not part of outdoor nature. But, you know, bebop is an urban music so there was definitely a challenge trying to compose music with the rural setting. But it was also part of the beauty of the situation, and opportunity to combine the two worlds—which is a notion I never would have thought of before my time out there.

AAJ: In some of the most experimental interpretations of Parker’s work, you use sputtering and vibration—literally spitting air through the mouthpiece of the horn. What was your intention of expression there?

JI: Well, in the liner notes I have a quote from Sonny Rollins. I had a chance to interview Sonny Rollins several years ago and we were talking about Charlie Parker’s sound. While everybody gravitated toward the speed and dexterity of Parker’s playing, Rollins said that it was the spirit of the way Parker played that suggested freedom. Obviously in the sixties, Rollins went as free as any jazz musician had ever gone. So I’ve always used that [Rollins’ quote] as my inspiration. Jazz means freedom. I was definitely trying to make the tenor do different things, exploring with blowing into different parts of it—just trying everything. For me, that’s part of the tradition at this point, because that’s what Rollins and Ornette Coleman and these guys were doing. So, for me, I wasn’t just going to do an album with just a dozen Charlie Parker tunes. That didn’t make any sense to me. I don’t normally include these experiments in my other records. But some of these tunes I just stumbled across—like “Mohawk” is a flutter exercise for me and I keep this continual flutter tone going while improvising on the form. Those tunes combine a lot of different aspects where I’m experimenting but also joining it with timing changes. I felt getting four experimental tracks through a Charlie Parker head was a big accomplishment for myself.

AAJ: Do you choose a different time signature when you play one of these Parker standards or does that become more spontaneous?

JI: Over the course of me being out there, I was playing all these heads to get my tenor going—trying to get a bigger sound going. I was really experimenting with different time signatures, tempos—and all of it. By the time I decided in late summer and fall that I have to at least document this, I’m deciding, ok, which tunes do I put on the record and which to leave off. And then what kind of tempos, keys and different moods can I take each tune into, to make each song its own individual thing. Crafting an album, aside from being in the canyon, requires getting the beautiful timing right and a lot of the tunes are in B flat or F so how can I record these songs that I like and switch it up enough to make an interesting flow at least.

AAJ: You were just referring to the Sonny Rollins interview you did in 2016, and reflecting back on his legendary 1959-60 self-sabbatical on the Williamsburg Bridge in New York City—did that resonate with you in any way?

JI: Yeah, I sent the record to a couple of friends, and they all said, “oh yeah, it’s your Sonny Rollins ‘bridge’ time.” You know until they said that, I didn’t really equate the two—but ok, then I guess my version is going to this canyon. But his was obviously longer and he was in a perfect place in his career and left because he wasn’t satisfied with the way he was playing. It’s of course slightly different, as mine was a forced exile (fleeing Covid in New York City for South Dakota) and there were no gigs or recording sessions going on during that time period. But I do feel that I grew and changed during that time and now things are starting to open-up again, so I’m hoping that my playing has grown just like when he [Rollins] came back from the bridge. But there w as no premeditated thought process that this was my “bridge” moment, but I’m glad that it happened for this aspect anyways.

AAJ: From of this canyon-retreat experience, what have you learned about the natural environment as a source for inspiration and creativity?

JI: Every day I’d drive to the natural forest, hike around and start playing. So, I had a different vantage point of the same canyon over hundreds of times here in my six months there. So, even though it was the same canyon, every day was different. It was some days blindingly sunny and other days drizzling rain. Only cancelled one day due to rainstorm. Some days were super windy and had to embrace the wind and decide how to craft your sound around it. Some days it was still, and you couldn’t here any sounds. Some days there were military helicopters going over-head and motorcycles during the Sturges Motorcycle Rally and all you could hear was motorcycles. Some days a lot of deer and other days just flies everywhere. So I had to adapt even though the overall canvas was the same, every day felt slightly different, and it was a joy to experience all that and especially the change of the seasons. When I first started going out there, there was snow on the ground and then I went through the beautiful springtime and the blazing hot summer, and then the leaves were already changing by the time I recorded the record. I got to see all the seasons through the lens of that same camera, got to see it change four times. And I think the changes in my playing, over those months, were really subtle and influenced by the canyon -by kind of just letting it happen. As long as you’re paying attention, you can choose all these differences.