The limelight for the Big Band Era of Swing is often dominated by the familiarity of names such as Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Artie Shaw. Yet Fletcher Henderson was a pivotal bandleader, leading possibly the most dynamic early big band of the ‘20s and ‘30s and having been an enormous draw and popularity both in performances and recordings. As an early post-Dixieland/Ragtime innovator, he helped define the sound of Big Band Jazz. “Fletcher Henderson was pioneering musical ideas which today are taken for granted.” Credited with developing the transition from New Orleans Dixieland-style and its counterpart, Ragtime, Henderson is seen as the “architect of swing.” In terms of this jazz genre’s turning point, his compositions and arrangements mark this transition “from New Orleans jazz, with its spontaneous use of improvisation in a small band setting, to the big band setting of the swing era, with its more formal orchestral structure and arrangements.”

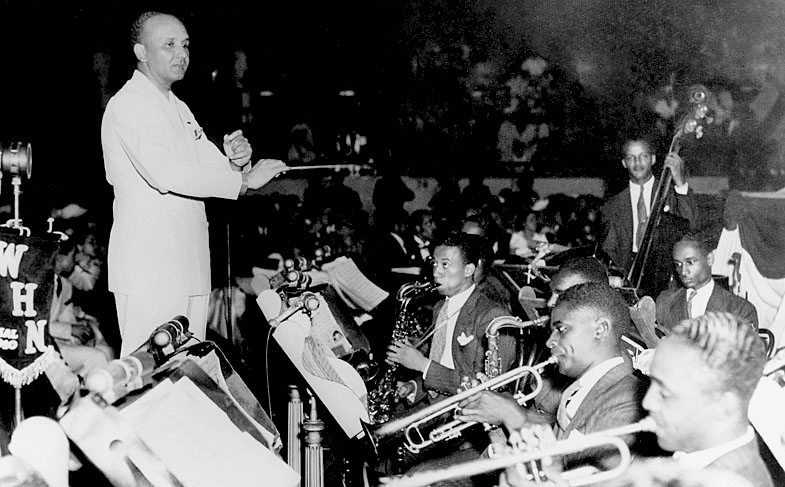

He formed his own band in 1921, which was in residence first at the Club Alabam, then at the Roseland Ballroom in New York City’s Theater District. Roseland was one of the top dance venue ballrooms in the Northeast and, along with Fletcher Henderson, all the biggest names in Swing were playing at this now-historic ballroom:

“From the 1920s to ‘30s, the crowds that packed the ballroom were ready to dance, and those dancers got to cut a rug to music by some of the biggest names to ever grace the stage, like Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Chick Webb, Harry James, Tommy Dorsey, Fletcher Henderson, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie (with his Roseland Shuffle) and the First Lady of Song herself, Ella Fitzgerald, and her recordings survive from 1940 (fronting the Chick Webb band). If the walls in that ballroom could talk, or sing, rather, they’d be echoing with the classic, swooning sounds that used to bring people from miles around.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roseland_Ballroom)

In a similar parallel to the Ellington/Strayhorn songwriting, arrangement, and orchestration partnership, Henderson would team with saxophonist and arranger Don Redman. Together, the two created an innovative and dynamic new concept for big bands. As stated in a 1999 article in the Washington Examiner, honoring the 100th anniversary of Ellington’s birth, Fletcher’s significance is recognized alongside The Duke. “They (Fletcher and Redman) all but invented the big-band sound. It’s hard to imagine the Swing Era without Henderson’s Sugar Foot Stomp and King Porter Stomp. In fact, Ellington acknowledged his debt to Henderson: “His was the band I always wanted mine to sound like when I got ready to have a big band, and that’s what we tried to achieve the first chance we had with that many musicians.”

The collaboration between Fletcher and Redman invented a much larger orchestra, enlarging the traditional sections of a big band, as recognized by jazz historian Gunther Schuller: “by taking a woodwind instrument, clarinet and two brass instruments, trumpet and trombone, and just expanded that…they wanted to make the sound bigger and fuller and richer with more colors.” In many ways, Fletcher had constructed a template of how to expand instrument sections beyond the current standard and is recognized, retrospectively, as a true innovator – bringing a “bigger” sound to swing. Accordingly, jazz critics cite Henderson as the first band leader to enjoy real success, leading perhaps the best and most important jazz band of the late Twenties.

Another significant impact of Fletcher’s orchestra was the star talent that was featured, which helped establish the early careers and earning fame for several now-legendary jazz musicians including Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, J. C. Higginbotham, Bix Beiderbecke, Roy Eldridge, Frank Trumbauer, and Rex Stewart. Additionally, in the 1940s, prominent free jazz band leader Sun Ra also worked as an arranger during Henderson’s engagement at the Club De Lisa in Chicago.

Armstrong’s intersection with Fletcher and his band was to serve to push both bandleader and featured horn player to a new intensity, with extended cornet solos by Armstrong that were pioneering:

“Henderson was able to steer his orchestra into the uncharted waters of hot big band jazz, combining Armstrong’s capacity as a jazz soloist with his own expertise at leading a large ensemble. Armstrong was not as musically literate as the other band members, but he was an accomplished and revolutionary soloist on cornet. Hearing him play daring solos in the dance music environment of the early Henderson years is an amazing experience.”

As the business side of running a big band required a “learning on the job” temperament, without the professional management assumed today, Henderson’s biography reveals his inability to maintain a profitable operation. In the mid-to-late ‘30s, with expenses mounting, Henderson began selling many of his arrangements to Benny Goodman. In 1939, Henderson disbanded his band and joined Goodman’s, first as pianist and arranger and then working full-time as staff arranger. Henderson’s career as a composer and arranger must therefore include recognition that this period represents his popularizing of songs that in fact were performed by Goodman’s orchestra, though Goodman always credited Henderson with the arrangements:

“Goodman who used them (Fletcher’s arrangements) to define the sound of his new orchestra. King Porter Stomp, Down South Camp Meetin’, Bugle Call Rag, Sometimes I’m Happy, and Wrappin’ It Up are among the Henderson arrangements that became Goodman hits.”

In 1936, Henderson would enjoy popularity again with an original composition, Christopher Columbus, which became his biggest hit released under his own name.

In the 1940s, Henderson would continue to contribute arrangements to Benny Goodman, Count Basie, and other big band leaders of the period. Clearly, these bandleaders not only benefited from the productivity of Henderson, but also the result of driving the popularity of swing for dance hall venues, radio shows and recordings. He had little success in the longevity of reforming his own bands to compete with the overwhelming success and audience attention of Ellington, Goodman, and Basie’s bands, and their talented lineup of soloists, but did tour with Ethel Waters in ‘48 and ‘49. By the 1950s, Henderson had formed a sextet that became the house band at New York’s Cafe Society. He would suffer a stroke that same year and be forced to retire. He died two years later at the age of 55.

From an historical point of view, in the swing era driven by big band orchestration, Henderson’s arrangements (along with collaborations with Don Redman) are recognized as a blueprint for this genre of jazz music. From a contemporary standpoint, past modern big band orchestra leaders such as Sun Ra and Bob Brookmeyer, as well as current contemporary composers, arrangers and bandleaders like Maria Schneider and Darcy James Argue, all follow some form of the “swing” template originated from Henderson. His influential legacy can be further explored with existing recordings and documentaries (particularly the Fletcher Henderson CD and Ken Burns’ 10-part Jazz documentary, specifically Pt. 5 & 6). As put in more direct and emotional terms, by saxophone tenor great Coleman Hawkins (in reference to Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra), “It was a stompin’ band… yeah man, a stompin’ band!”