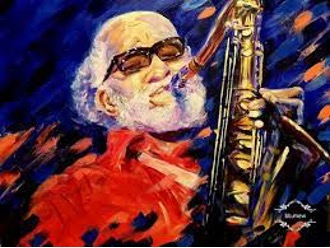

If you happened to be on the Williamsburg Bridge anytime from the summer of 1959 through roughly the autumn of 1961, you would have been privileged to hear the sound of a true artist seeking to find new directions and an inner voice on his instrument. Already famous and successful, with constant performing and recording, Sonny Rollins, one of the greatest tenor saxophonists of the Bebop and hard bop eras, had left the public eye, working out his notes alone on the bridge, to find a new conversation with his horn. He would later record The Bridge, his 1962 comeback album, a direct inspiration, and result of this sabbatical. Rollins’ shift to a more narrative voice and stream of consciousness style on his saxophone would be highly influential, impacting all other jazz horn players to follow.

His apprenticeship and exposure to music harks back to a childhood in the 1940s, surrounded by music-loving parents of West Indies ancestry, growing up in Harlem and Sugar Hill, New York City. Rollins absorbed the music he heard around him, finding an enormous capacity for recalling songs and melodies, coupled with an incredible natural playing talent. Moving from the piano to the saxophone at about 7 years old, as the account is told, an uncle named Hubert Myers, who was a professional saxophonist, helped Rollins pick out his first horn. “ I used to play for hours and hours at home,” Rollins recalled in an interview. “I was in my own world. My own reverie. I did a lot of free association, just ideas came to my mind, which is why I have told people- that I consider myself a free musician.”

Mostly a self-taught musician, by 1956 at the age of 26, Rollins had already played and/or recorded with Bebop giants Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and J.J. Johnson and had established himself as a prominent young voice on his instrument via recordings and performances as a leader.

In 1956 Rollins also made his biggest move in terms of early apprenticeship and musical development, joining the famous ensemble, the Max Roach-Clifford Brown Quintet, while also working with Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk during this same period. Seemingly undaunted by established and renowned band leaders and still only in his late 20s, Rollins began accentuating his own inventive voice. As stated on his website biography, “his trademark became a caustic, almost humorous style of melodic invention, a command of everything from the most arcane ballads to calypsos, and an overriding logic in his playing for models of thematic improvisation.” (www.sonnyrollins.com/biography)

During this same period, a very intense burst of recordings with Prestige Records was occurring, with varying stellar musicians and bandleaders including Davis, Monk, and rising star John Coltrane. Rollins would further establish and cement his reputation as an innovator on his instrument in solos and composition, particularly with the now legendary recording of Saxophone Collosus (1956) and also Tenor Madness(1956) using Davis’ band and John Coltrane on the title cut.

His next step in 1957 was a bold pioneering statement of independence, both as a bandleader and innovator of his instrument. With bassist Wilbur Ware, (alternating with Donald Bailey) and drummer Elvin Bishop (alternating with Pete La Roca), Rollins had created a trio arrangement in jazz, without a piano. His recordings with this unconventional trio arrangement with experimental time signatures (including Way out West, Wagon Wheels, I’m an Old Cowhand, and It Could Happen to You), demonstrated Rollins’ willingness to take chances, using simple hackneyed song melodies and improvising to deliver a jazz interpretation. All these recordings represented an experimental departure, which Gunther Schuller (renowned jazz musician, composer, teacher, and founder of jazz studies at New England Conservatory) hailed as “demonstrating a new manner of thematic improvisation.”

During the years of 1956-1959, Rollins had found fame, performing constantly, and was widely regarded as the most talented and innovative tenor saxophonist in jazz. It was exactly at this moment that Rollins then decided to step away from all public performances and recordings. As he explained in a 1961 interview in The New Yorker, “People (jazz musicians) are not doing things as well as they can do them anymore; the extraneous things had gotten in the way of it. I didn’t have time to practice, and I wanted to study more. I was playing before more and more people, and not being able to do my best. There was no doubt that I had to leave the scene.” For over a year Rollins would seek refuge on the Williamsburg Bridge in New York City, not far from his address on the Lower East Side, playing sometimes 14 to 15 hours a day, working to find a new direction and voice for his artistry as a musician.

His comeback release, The Bridge (1961), with jazz guitarist Jim Hall, would reveal a revolutionary change in technique, and become a wide commercial success (also receiving a Grammy Hall of Fame award in 2015). The most indicative sign of style-change and substance was his live performances during the mid-60s, which became “grand, marathon stream-of-consciousness solos where he would call forth melodies from his encyclopedic knowledge of popular songs, including startling segues and sometimes barely visiting one theme before surging dazzling variations upon the next.” (www.sonnyrollins.com) Throughout the last half of the 60s, he further sought out collaborations with Jim Hall, Don Cherry, Paul Bley, and his idol, Coleman Hawkins.

With his recording contract with RCA Victor (1962-1964), Rollins explored and experimented with a variety of musical influences including Latin rhythms (What’s New?), avant-garde (Our Man in Jazz), “free” jazz (Sonny Meets Hawk!) and reexamined jazz standards and the Great American Songbook.

By 1966, Rollins was again seeking time away from performing and the constant demands on him personally and professionally. In 1963, he made the first of many tours to Japan, exposing himself to eastern culture, later choosing to live in an Indian monastery and eventually returning to Jamaica to study yoga, meditation, and Eastern philosophies from 1969 – 71. Rollins explains his feelings, from excerpts from his biography (sonnyrollins.com), “I was getting into Eastern Religion…I’ve always been my own man. I’ve always done, tried to do, what I wanted to do for myself. So these are things I wanted to do. I wanted to go on the Bridge. I wanted to get into religion. I took some time off to get myself together.”

Returning to performing in ‘72, with strong encouragement and support from his wife Lucille, who had become his business manager, Rollins began a seminal recording period with producer Orrin Keepnews for Milestone Records. Reinvigorated from his 2nd sabbatical, Rollins surrounded himself with exceptional talent, including all-star ensemble recordings with Tommy Flanagan, Jack DeJohnette, Stanley Clarke, and Tony Williams to making several tour recordings with McCoy Tyner, Ron Carter, and Al Foster of the Milestone JazzStars.

Post 2nd sabbatical, critical attention was on Rollins’ evolving sound, as young jazz bandleaders like Chick Corea, Larry Coryell, Joe Zawinul, and John McLaughlin were moving to incorporate rock with jazz. In New Leader, jazz music critic Bruce Cook observed, “an increasing coarser and rougher tone, influenced by the variety possible with fusion.” Rollins, awarded a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship in 1972, was more direct, “You have to change as you hear different sounds…I like to think of myself as relating to all these things, not just some guy who made great records in the fifties.” His 1978 release Don’t Stop the Carnival, and other albums of the 80s, pushed further in this direction, with increased use of electronics and rock. (per Rollins jazz bio from www.encyclopedia.com)

In a DownBeat interview at the close of the 80s, Gene Kalbacher designated Rollins “the world’s greatest living improviser,” paying tribute to the musician’s ability to take a tune like “There’s No Business Like Show Business” and “tenderize the unlikely song into a jazz vehicle.”

Though critics’ reactions to Rollins albums of the late 80s and early 90s were mixed, the musician continued to stun fans with his live performances. People contributor David Grogan watched Rollins “nearly blow” Branford Marsalis off of the Carnegie Hall stage at a live concert. And when Grogan reviewed the album Falling in Love With Jazz, he concluded, “No one is better than Rollins when it comes to transforming a familiar melody into an occasion for utter astonishment.” (per Rollins jazz bio www.encyclopedia.com).

Through the 1990s and into 2000, Rollins continued to tour internationally with enormous popularity, and also recorded many of these later year performances, archiving over 250 concerts.

Retiring from performance in 2012 due to respiratory health issues, and now 91 years old, Rollins has deservedly earned all of his accolades, acclaim, and awards. He delivered decades of influence upon jazz directions and acted as a musical, social, and political change agent with his horn. In recordings and performances, he was always pushing to find a new level or direction, leaving a high bar to follow for his instrument. He is a standard-bearer in every way, with an ongoing impact on present-day jazz musicians.

Having received almost every award for musicianship, composition, artistry, lifetime contribution, and breadth of accomplishment, the following shortlist of highlighted awards confirms this depth of professional recognition: Down Beat Jazz Hall Of Fame (1973), Honorary Doctorate of Music from New England Conservatory of Music (2002), Honorary Doctor of Music from Berklee College of Music (2003), Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement (2004), Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement (2006), National Medal of Arts (2010), Elected to the American Academy of the Arts and Sciences (2010), Kennedy Center Honors on his 81st birthday (September 7, 2011), Honorary Doctor of Music from Juilliard School (2013) and the Edward MacDowell Medal (2010).

However, harking back to the image of the solitary man, on a bridge – often at night, working on improving and innovating his craft, sometimes 15 hours a day – this is the most fitting metaphor of Rollins’ character. As a constant innovator of his saxophone voice and fierce individualism in commitment to his own integrity and standards, Rollins not only remains a “colossus” figure in jazz and to his peers, but also a mentor for the arts and humanities.